[1] Cf. using the example of Lippe navigation Bremer, Nutzung des Wasserweges, pp. 88.

[2] Quoted from Santel, Fons padulus, p. 4.

[3] Coming from Neuhaus, these were the following obstacles: the two inner-city crossings at the (a) four-arched bridge at the „Lipper Tor“, (b) the three-arched „Nepomukbrücke“ at the Paderborner Tor (Old Waterworks) as well as the (c) two-arched „Steinbrücke“ ( „pons lapideus“) at the upper reaches of the Pader shortly before the „Paderborner Wassertor“.

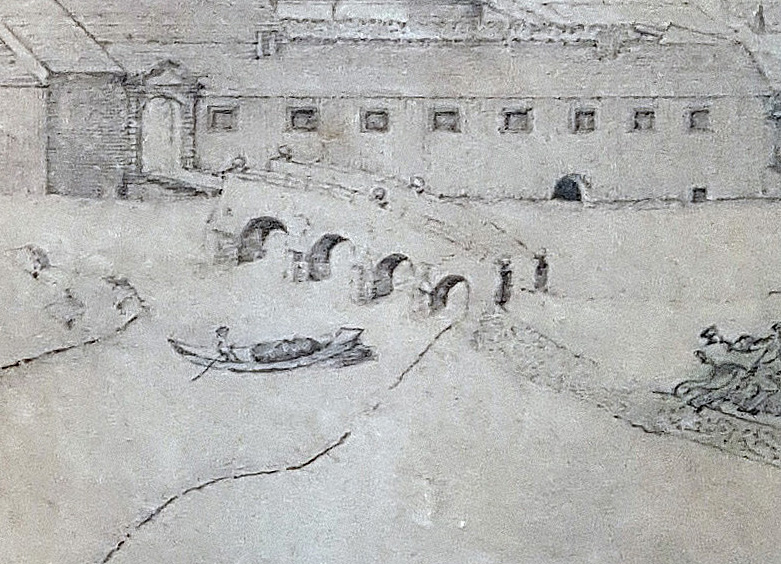

[4] Cf. C. Schlauns Neuhäuser Prospekt (1719).

[5] Cf. a. o. photo taken around 1900 by W. Lange, Soest, Sammlung Golücke, StadtA Pb, S – M 4 D, No. 3628.

[6] On making the Lippe navigable in the 19th century, cf. Bremer, Nutzung des Wasserweges, p. 24ff. As early as 1830, Chief President von Vincke inspected Neuhaus as a potential final port for shipping on the Lippe. On 31 August 1832 he personally set sail from the Lippe bridge with a ship to travel via Boke to Lippstadt. Cf. excerpts from the local chronicle in Pavlicic, Michael: Neuhaus und die Lippeschiffahrt im 19. Jahrhundert, in: Die Residenz 92 (1989), pp. 11.

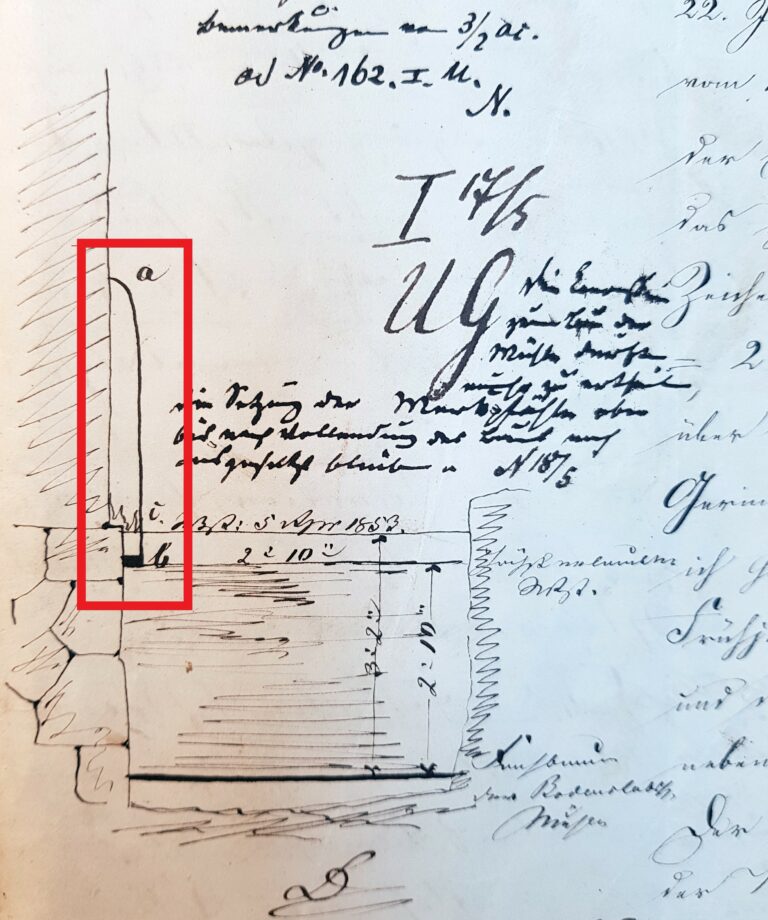

[7] Cf. copy of the assessment from the Minden government to Landrat von Spiegel in Paderborn, 2 March 1832. LA Detmold, M 1 I U, No. 660, unfol. A „Situations Plan von den F. Müller gehörigen an der Pader in Neuhaus belegenen Mühlen“ (Situation plan of the mills belonging to the F. Müller on the Pader in Neuhaus) records the alterations carried out in 1855. StadtA Pb(?), W6/ 66.

[8] Cf. Müller, Rolf-Dieter: Erstes Frachtschiff nach Schloß Neuhaus getreidelt. Strom- und Uferordnung für die Lippe, in: Die Warte 46 (1985), p. 12.

[9] Cf. Wurm, Neuhaus, pp. 81.

[10] In 1890, the floods of the swollen „Wasserkunstpader“ tore away the stone „Nepomukbrücke“. Cf. Santel, Baugeschichte des Hauses Scherpel, p. 41. On the history of the statue of the bridge saint from the Seven Years’ War, cf. Hansmann, Wolfgang: Die Statue des hl. Johannes Nepomuk an der Paderbrücke, in: Die Residenz 92 (1989), pp. 3-9.

[11] Cf. imprint in the official gazette, LA Detmold, M 1 III E, No. 151, unfol.

[12] „§ 9: The clear width of the openings of the bridges and footbridges, after deduction of the thickness of the central piers and yokes, must correspond to the prescribed width of the bed and the track must be at least 2 feet above the mean water level, unless the viewing committee declares a lower height […] to be permissible.“ LA Detmold, M 1 III E, Nr. 151, unfol.

[13] Cf. Müller, Erstes Frachtschiff, p. 12.