[1] Cf. Winter, Franz Josef: Schloß Neuhaus in alten Ansichten, Zaltbommel 1984, Fig. 24.

[2] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Ämterrechnungen Neuhaus (1596/97), Nr. 1046, fol. 46r. The previous assumption that the princely fulling mill was a new Baroque building, according to a dated coat of arms stone (1716) that Prince-Bishop Franz Arnold von Wolff-Metternich had attached to the canal above the mill gate, must therefore be critically questioned. Cf. Middeke, Josef: Bild der Heimat, in: Die Residenz 5/25 (1966), p. 1-7; here p. 5; Winter, Schloß Neuhaus, Fig. 24.

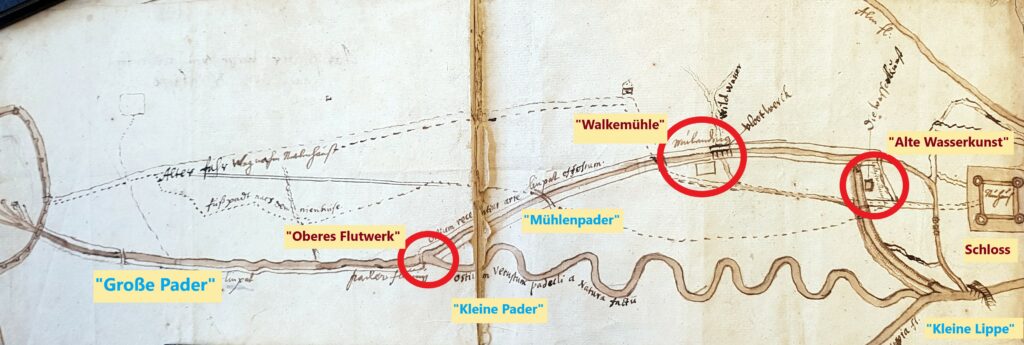

[3] Cf. „Abriß der Wege von Paderborn nach dem Nienhuiße“ in Koch, Frühe Verkehrsstraßen, pp. 248, Fig. 71.

[4] Cf. Rade, Bewohner, p. 27.

[5] Cf. for the accounting year 1603/04: LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Ämterrechnungen Neuhaus Nr. 1046, fol. 106r-111r.

[6] Cf. Beschwerdeschrift der Wandmacher, o. D. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 354, fol. 114r-114v.

[7] Ibid.

[8] LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 765, fol. 22r-23v.

[9] „Newhausischer Mühlen Contract“, 21. Mär. 1711. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 765, fol. 14r-16v.

[10] Vgl. Art. 6, lease agreement of 15 June 1733: „[…] Finally, the millers are also seriously ordered to manage the water in such a way that the princely mill at Newhauß does not lose any of it, to which end they should also be committed, to take good care of the topmost waterworks, so that the same is always provided with the necessary water, and to supply the water in such a way that the necessary water is led into the mill river [Mühlenpader], and no harmful overflow may be caused.[…].“ LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 765, fol. 23v.

[11] „Unterthänige Bittschrift“, undated (around 1789). LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 3044, fol. 30r-32v.

[12] Ibid., fol. 30v. In August 1798, the tenant Simon Fromme, who had taken over the fulling mill in 1783, claimed to the court chamber that his predecessor Ferdinand Tewes had let the mill, including the tidal mechanism, fall into disrepair due to „incapacity“. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 766, fol. 1v-3v.

[13] Cf. lease agreement of Simon Fromme, undated (end of 1783). LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 765, fol. 39r-39v.

[14] The cost estimate explicitly mentions: Renewal of two wooden stamps made of beech wood, repair of the wheel chair, manufacture of a new water wheel, replacement of various supports on the northern half-timbered wall, new roof covering. LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 766, fol. 9r-12v.

[15] Cf. lease agreement of 21 October 1799, LA Münster, Fürstbistum Pb, Hofkammer Nr. 766, fol. 14r-15r.

[16] Ibid., Art. 2, fol. 14v.

[17] Preußische Ortschronik für Neuhaus (1818/19). StadtA Pb, H Schloß Neuhaus -1, pp. 5.

[18] Cf. ibid., p. 18; Wurm, Neuhaus, pp. 71.

[19] Cf. letter by the miller Louis Gockel to Amtmann Christiani zu Neuhaus, 13 April 1858. LA Detmold, M1 III E, Nr. 151, unfol.

[20] Mutterrolle (1832), LA Detmold, M 5 C, Nr. 1469, No. 14.

[21] Cf. application of the mill owner Louis Gockel to the district government of Minden, 30 January 1860. LA Detmold, Regierung Minden I U, Nr. 659, unfol.

[22] Cf. Mutterrolle of the Neuhaus cadastre (1867): While Louis Gockel is still listed as miller and owner of the fulling mill in 1867, Friedrich Müller is entered as the new mill owner „pro 1875“. LA Detmold, M 5 C, Nr. 5371, Art. 208.

[23] Cf. testimonial of the widow of Fritz Müller, interrogation transcript of 14 November 1925, trial file Thombansen ./. Rosenthal (1924/25). StadtA Pb, A 3713, unfol.

[24] Cf. Schäfers, Standorte, p. 85; Winter, Schloß Neuhaus, Fig. 24.

[25] In 1925, in addition to the widow Minna Müller, the merchant Franz Osthoff and Wilhelm Ottenlips lived here with his family. Cf. trial file Thombansen v. Rosenthal (1924/25), interrogation transcript of 14 November 1925. StadtA Pb, A 3713, unfol.

!["Die Walch-Mühle" from Christoff Weigel: Abbildung Der Gemein-Nützlichen Haupt=Stände [...], Regensburg 1698.](https://paderpedia.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Abb.-26_Walchmühle-676x1024.jpg)